Crop conditions and weather

The big weather event from this past week was all of the heat, heat, heat!

Crops continue to look promising as they move into their reproductive stages, when flowers develop and begin the process of seed formation.

Canola is flowering and now is the best time to visibly see how big of a canola-producer (and exporter) Saskatchewan really is. Flowering is still in the early stages, at approximately 30% bloom.

Wheat is heading out and very soon will begin to develop and fill seeds in the heads. Soil moisture and rainfall is very important for the grain-filling process in the weeks to come.

What's going on in the field

We have now entered ‘fungicide season’. Fungicides are not used every year when growing crops, but in years where we’ve seen higher rainfall, there is a higher risk of disease and farmers are more likely to apply fungicides in order to protect their investment. Fungicides can be applied by ground sprayers or by airplane.

At the flowering stage of canola, the disease of concern is Sclerotinia stem rot. Sclerotinia spores blow onto the flower petals of canola. When the petals drop, they fall into the branches of the plant and the fungus grows into the plant, using the canola petal as a food source. As the fungus develops, it kills the tissue at its entry point into the plant, and the entire canola stem above that point will be killed. This means that the farmer will not be able to harvest seeds from the killed branch, resulting in yield loss. The goal of a fungicide application at this stage is to spray the flower petals before they drop into the branches of the plant, which starts occurring at around 30% bloom.

For more information on Sclerotinia stem rot, visit the Canola Council of Canada’s Canola Encyclopedia here: https://www.canolacouncil.org/canola-encyclopedia/diseases/sclerotinia-stem-rot/

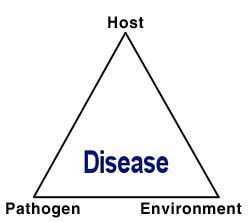

Because of the amount of canola and wheat that we grow year after year in northern Saskatchewan, the host crops and their common pathogens are usually present in the area. This means that the biggest influence on disease development is the environmental conditions. Sclerotinia and Fusarium both like moist and humid conditions, and while Sclerotinia likes temperatures a little cooler (20-25C), Fusarium thrives under warmer temperatures (up to 30C).

Even though the infection process starts now, the disease symptoms for both Sclerotinia and Fusarium show up later on during the crop’s life (in about August). So farmers have the tough decision of figuring out if they should be spraying for these diseases right now, since they can’t actually see if the disease is present or not at the time of spraying. The biggest influencer when making this decision is the weather (environment). We’ve seen good moisture so far this season, which favours disease, but this past week has been extremely hot with no rainfall, which is not favourable for disease. The crop is now at the correct staging for fungicide application, so it’s now or never - how does a farmer decide what to do? Taking a walk into the field will help get an assessment of how humid the canopy is. Good crop establishment will create a more lush, dense canopy that creates its own microclimate below - when you feel down into a dense canopy, the temperature is cooler than the air above and it’s more humid as moisture from the respiring leaves and soil evaporation gets trapped down there. So, if you’re walking through a field at 2:00 pm on a +30C day and your boots are wet when you come out, this is still an environment that disease can develop in. The questions that follow are, “will that canopy stay humid like that or not?”, and “is there more rain in the forecast?”

There are tools available to help farmers make fungicide application decisions, like the Sclerotinia checklist (see Canola Council link above) or the new FHB risk mapping tool (https://prairiefhb.ca/).

Ultimately, each farmer will have a different management style toward using fungicides for disease management. Some view fungicides as an insurance policy, where it’s penciled into their costs with the aim of protecting their investment (crop), knowing that in big disease years, the application will really pay off, and in lesser disease years, they hope to break even to cover the costs. Some will choose to spray some fields and not others, or some crops (like higher-valued canola) and not others (like wheat), if they feel that disease pressure might not be too bad. Some will spray none because they’ve already poured a lot of money into the crop and don’t want to incur another expense, and are okay with giving up yield if it turns out to be a disease year. In the end, the decision of “to spray or not to spray” involves many different factors (agronomic, economic, logistic, personal experience, management style), and is typically, like with any difficult decision, not a clear “yes” or “no”.